Are our historical objects safe in museums?

Relatively, one might say. Isn’t it better than being locked inside a windowless room, in solitary confinement, never to see the light of day?

I would agree especially since the Indian government, especially state government are known for their apathetic response to portable heritage. It is a well-known fact that a lot of historical sculptures especially bronze statues that have been returned to India from western museums and private collections are at present literally rotting (from bronze disease) in government storage facilities across the country. (For more on bronze disease, click here.)

But even when conservatorially safe as displayed objects in museum collections in India and abroad, their precarity takes on other forms. As someone who has spent what feels like a lifetime in museums across the world in the last few years, I strongly believe that precarity of historical objects stem from human and scholarly apathy. One particular story of precarity is discussed in this post - the precarity arising from lack of historical knowledge.

Prince William and Queen Victoria’s Ivory Throne

Official portrait of Queen Victoria as ‘Empress of India’ on the Travancore ivory throne, 1876. Image Courtesy: Royal Collection Trust, UK

In 2014, a huge brouhaha followed a surprise announcement by Prince William of UK: he suggested that as a symbolic warning to ivory poachers in Africa and elsewhere, all historic ivory objects in the Royal Collections Trust should be burned and destroyed. While wildlife conservationists applauded this decision, museum professionals were aghast, saying that such a move would take historical objects and make them into “artworks of shame.” In the following years, there have been calls to consider “reason, not passion,” when thinking of solutions for ivory poaching.

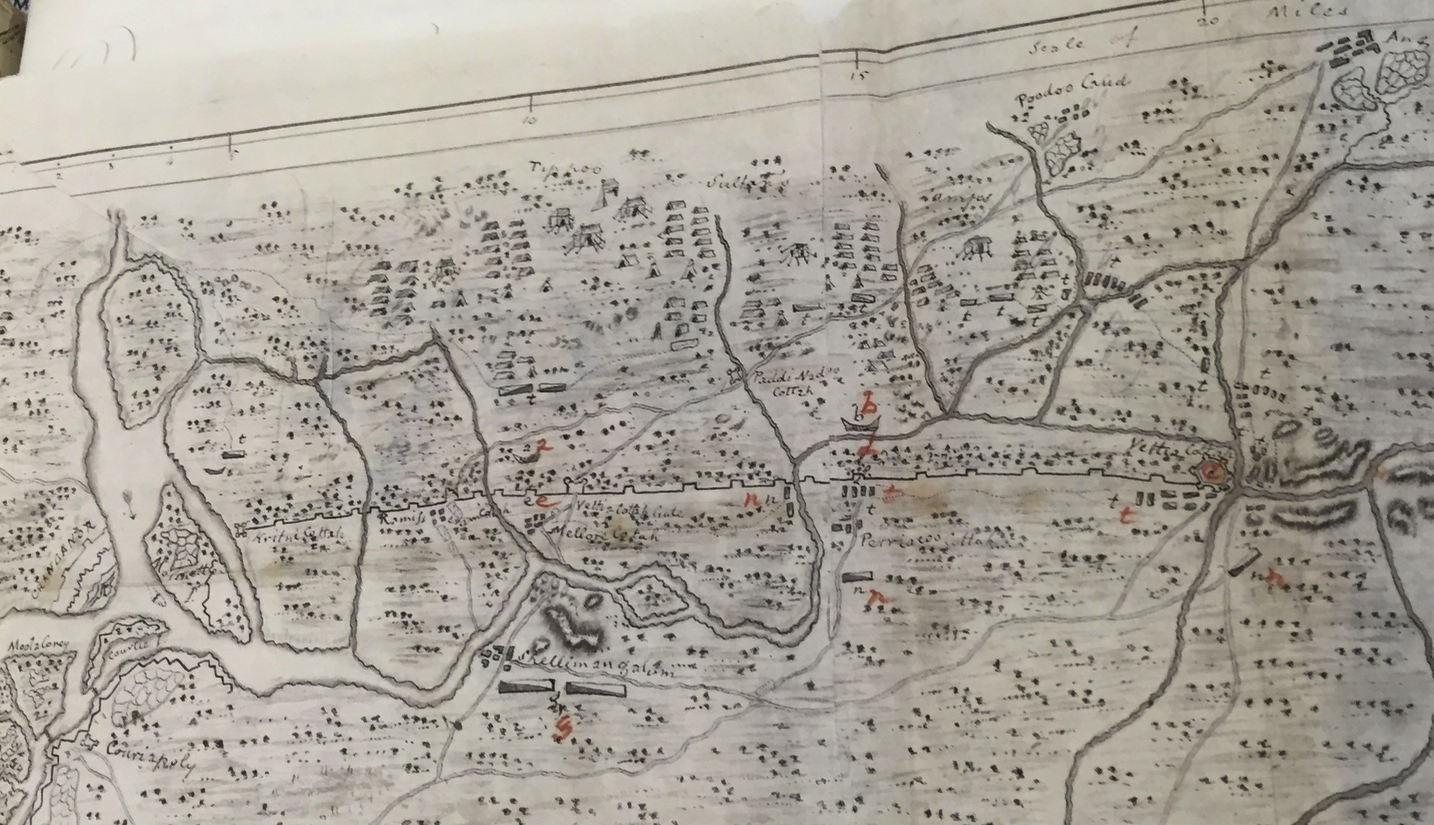

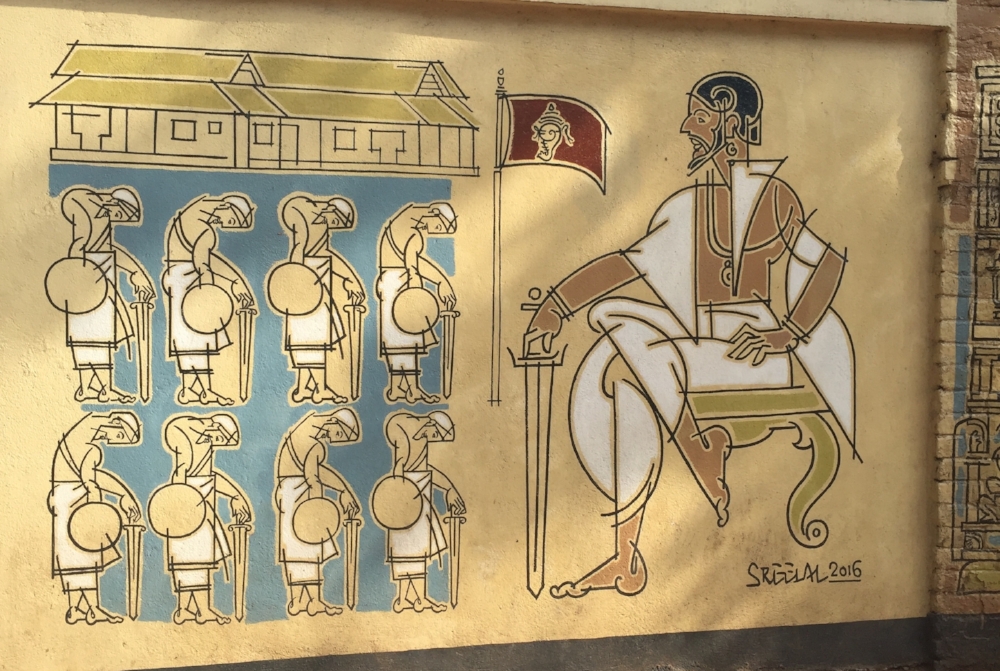

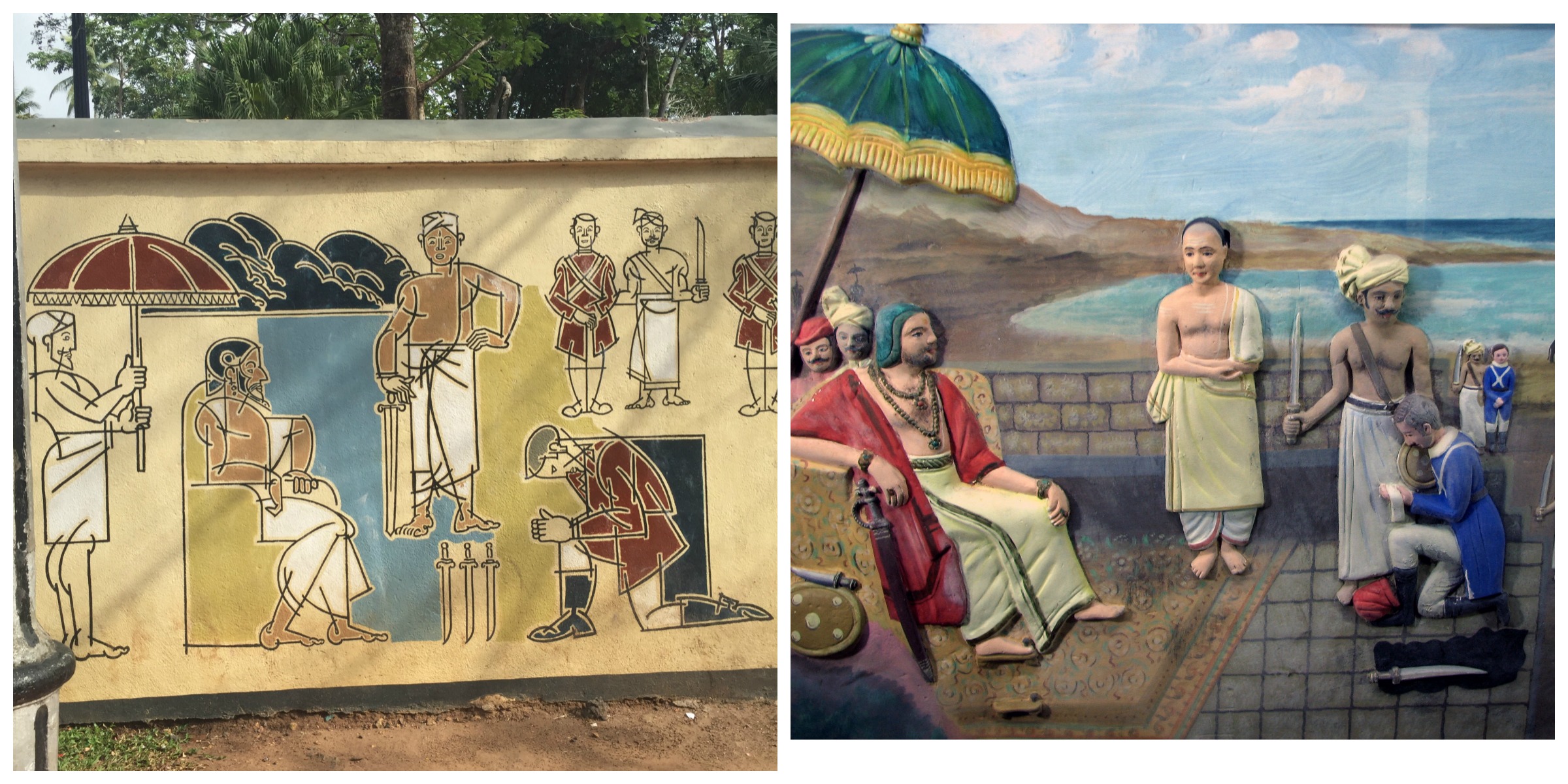

Mired in this tussle was one of the most prominent objects in the royal collection—the ivory throne of Queen Victoria. Newspapers after newspapers produced the resplendent watercolor image of the throne in full royal display at The Great Exhibition of 1851 when it was exhibited. The throne was a gift object presented to Queen Victoria by king Uthram Thirunal Marthanda Varma of Travancore, part of the modern state of Kerala, India. Completely worked by ivory carvers from the region and explicitly made as an objects of mediation and diplomacy, the throne in its function and structure is not British at all. It did, however, become an integral part of Queen Victoria’s interiors. Prince Albert, Royal Consort and beloved husband of the queen, used the throne as his presiding seat at the closing ceremony of The Great Exhibition, a program which he had patronized and helped bring to fruition. Perhaps it was this association with Prince Albert, but his widow chose this throne as her chair of state in 1876 when she was crowned The Empress of India. (You can read more about this throne in this post.)

Today the ivory throne is carted off and hidden from the Garter Throne Room in Windsor Castle when there are official dinners and other events so as to not politicize its presence and what it means to have such objects in the royal collection.

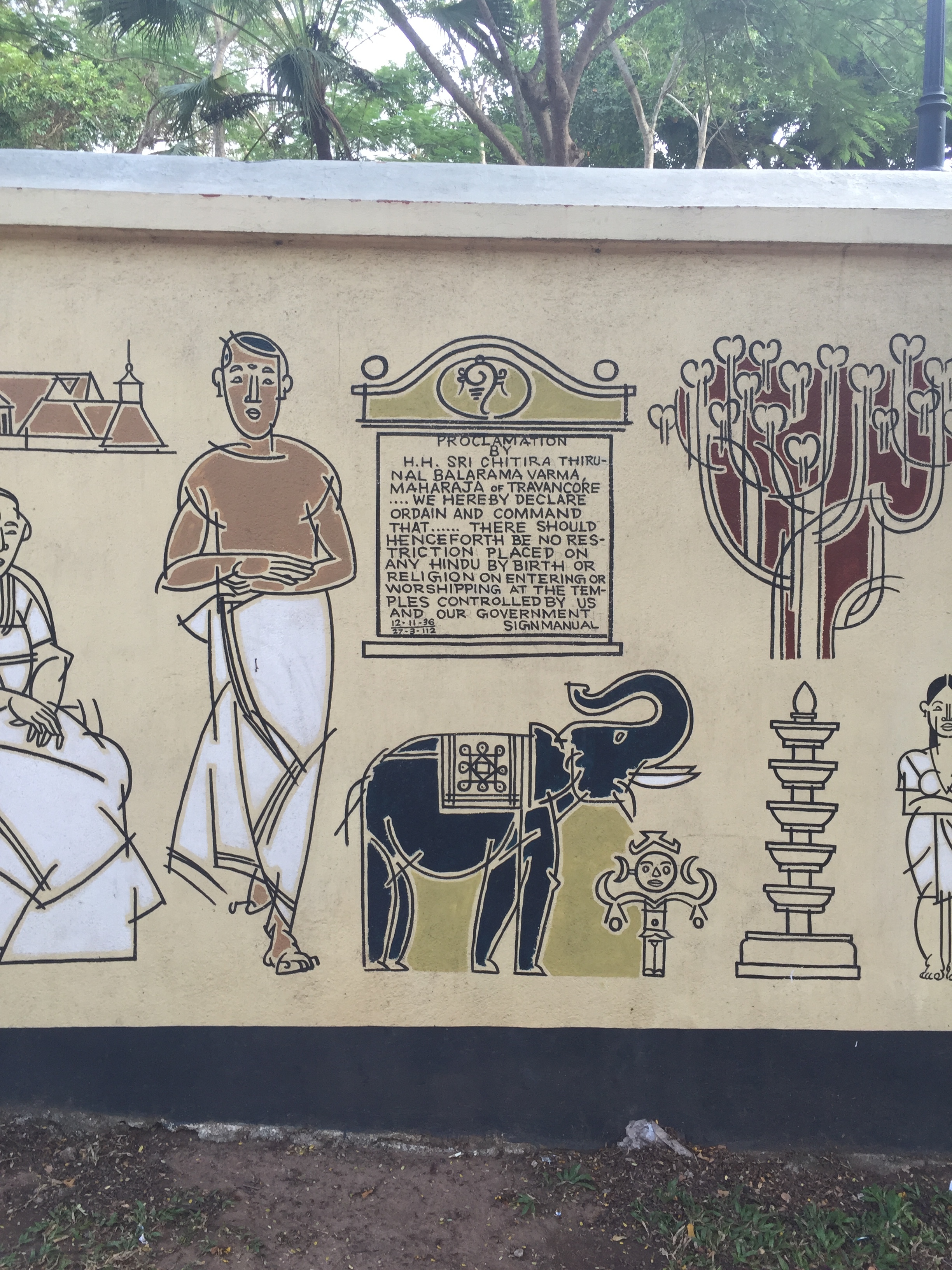

The call for its destruction and its erasure from the public eye during important events comes from the understanding that the throne is simply made of ivory and this material quality defines the object. In the course of studying this throne, I have come across documents that not only provide a colorful trail of stories of how the throne came to England but also a distinct understanding that the throne is not completely made of ivory as most people think it is. Its structure is of a particular type of wood (if you want to know what wood it is and where it came from, you will have to read my dissertation, available to public in a few months, I promise!). A good part of what is considered the material of ivory is not ivory from the tusk of the elephant but actually its teeth! In addition, the chance that the teeth came out of a domesticated elephant that naturally sheds its teeth six times in its life is higher than the alternative, that the teeth came from an elephant captured and killed for ivory. For in Kerala, elephants are a semi-venerated mammal, a very omnipresent animal important to temple activities across the state even today. While we can question the inhumaneness of taming an untameable wild animal, in Kerala, historically elephants where never actively killed for game. (This has since changed and poaching has been a serious issue in the last few decades.)

For our purposes here, the brouhaha about the throne and its threatened destruction is borne out a lack of knowledge about its materials and how it was produced.

There is also the sense that the throne is representative of only British monarchy when clearly it is as much an objects of Kerala as it is of Queen Victoria. Its material, design, patronage, and circulation originated from Travancore. It remains one of the premiery artistic objects made in the nineteenth century in Travancore. Its destruction would be a significant blow to an already understudied region whose artistic heritage is limited due to the prolific use of organic materials that are easily lost to time.

In the case of Queen Victoria’s ivory throne then production of historical knowledge is an ideal way to distance the throne from the discussion of ivory. The object is more than its material. For me, creation of knowledge is an activism and part of the project to preserve precarious objects like the ivory throne.

There are many other ways in which objects are in danger of being destroyed physically or erased from history. In the ethnonationalist world that we live in today, the presence of heritage objects become all the more necessary as visual reminders of the plural and interconnected cultures that came before us.

If you would like to see more on endangered objects, leave a comment below.