The walls around Kanakakunnu Palace grounds in Thiruvananthapuram have recently been beautified with murals, part of a city-wide project called Arteria (2014-16). Credited as one of the largest public art projects in India, the project includes handpainted murals of the postmodern variety, painted across walls lining many public spaces and institutions in the city. Many of the murals are painted to thematically complement the enclosed space's function. The project initiated in 2014 have had many prominent regional artists involved in its first phase.

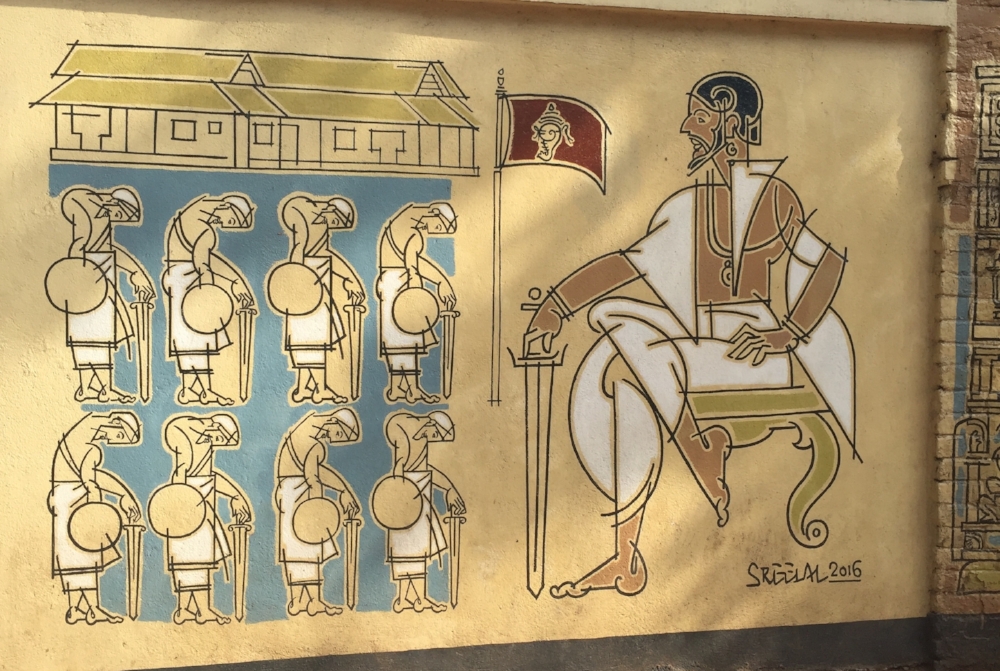

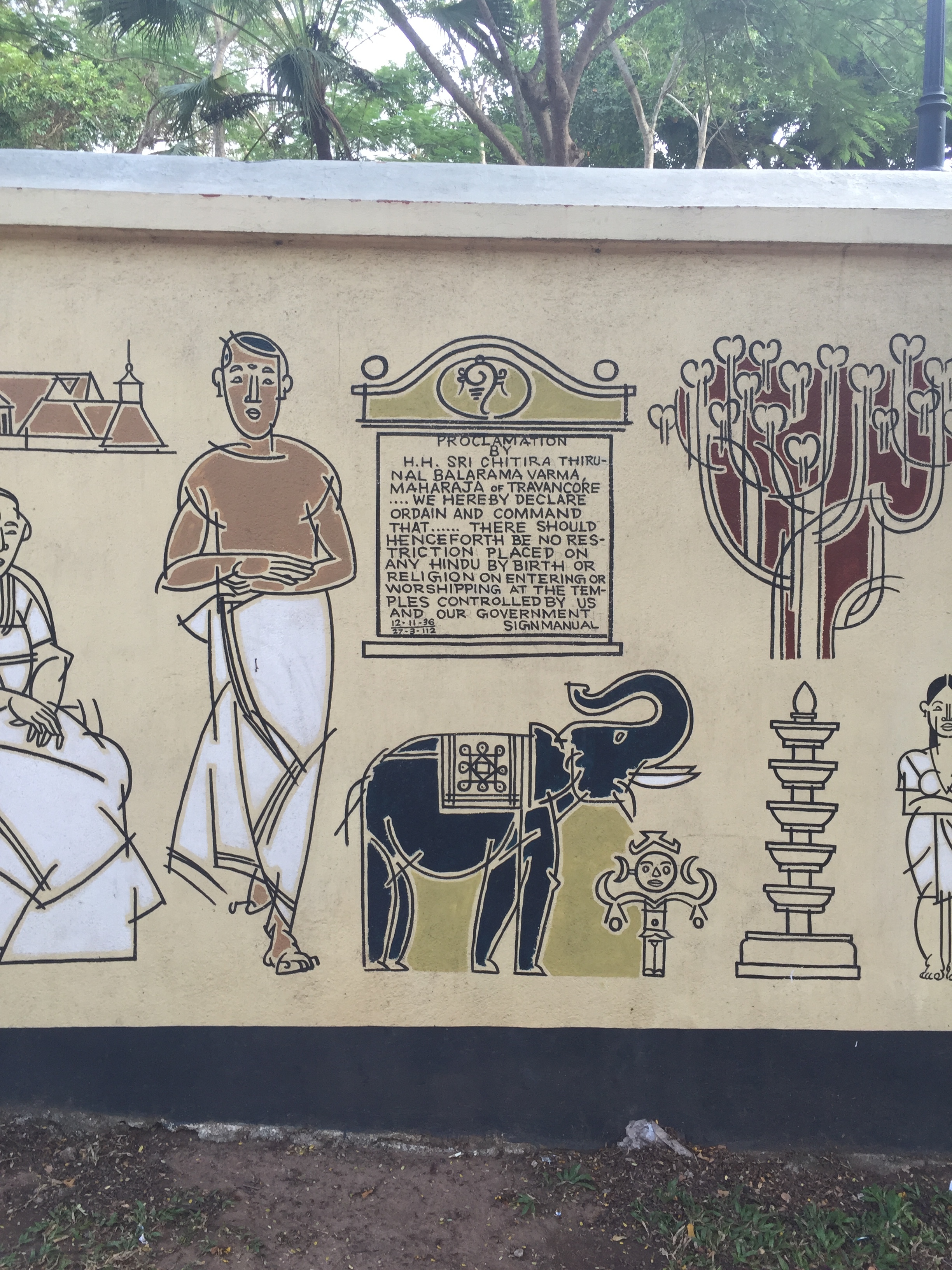

The Kanakakunnu walls stand apart from other mural projects as it is the only mural series showcasing the history of the state. Painted by Sreelal, the series depict various popular historical vignettes, from Travancore's inception as a modern state under Marthanda Varma in 1729 to its formative days as a state in postcolonial India during and after the reign of the last king Balarama Varma. What caught my attention was the particularized portrayal of Travancore through highly specific and easily identifiable historical events, that were rendered in an accessible pictorial style in one of the most frequented public spaces of the city.

(Click through the slideshow below for an abbreviated version of the history of Travancore as told by Arteria.)

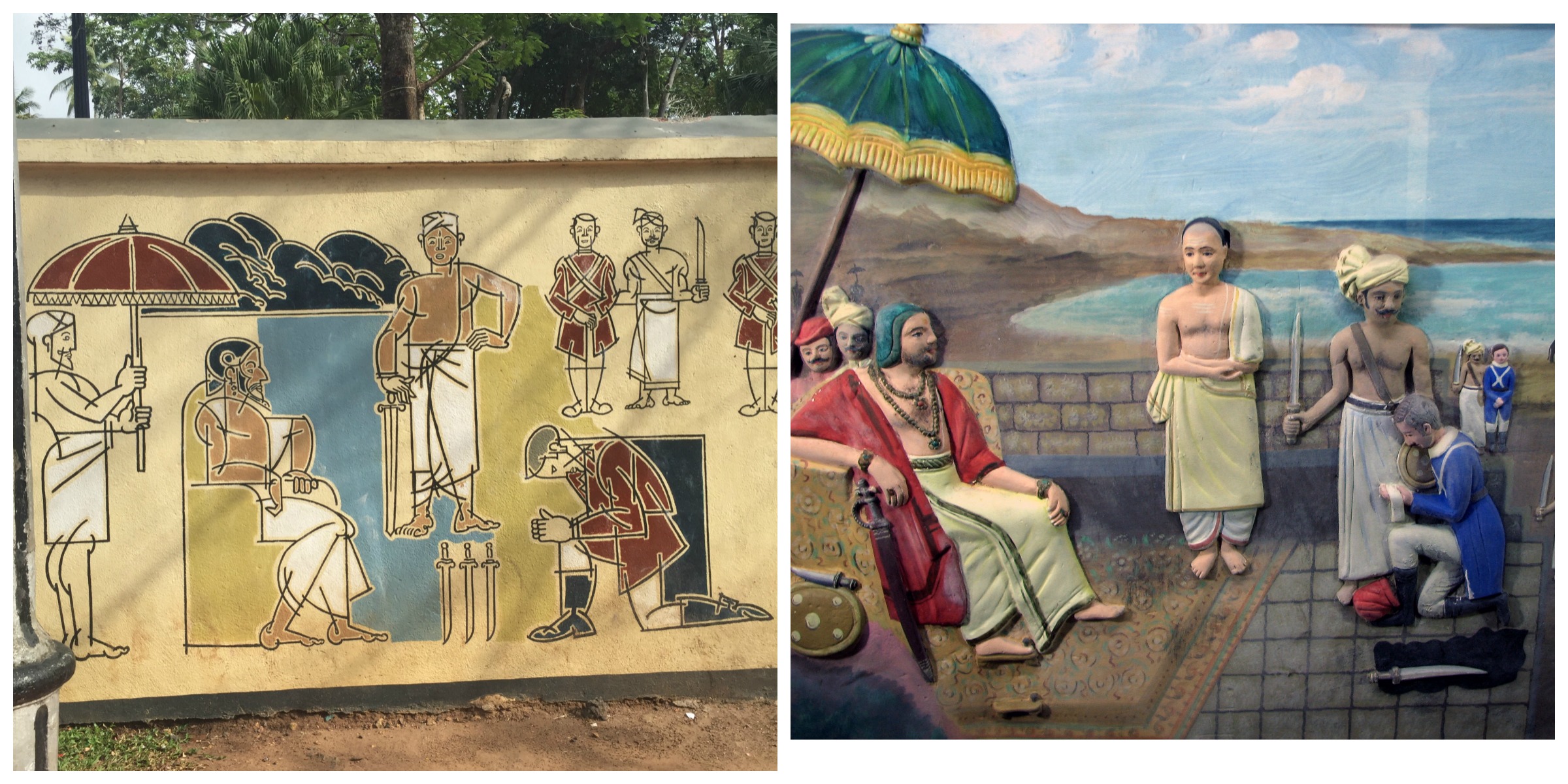

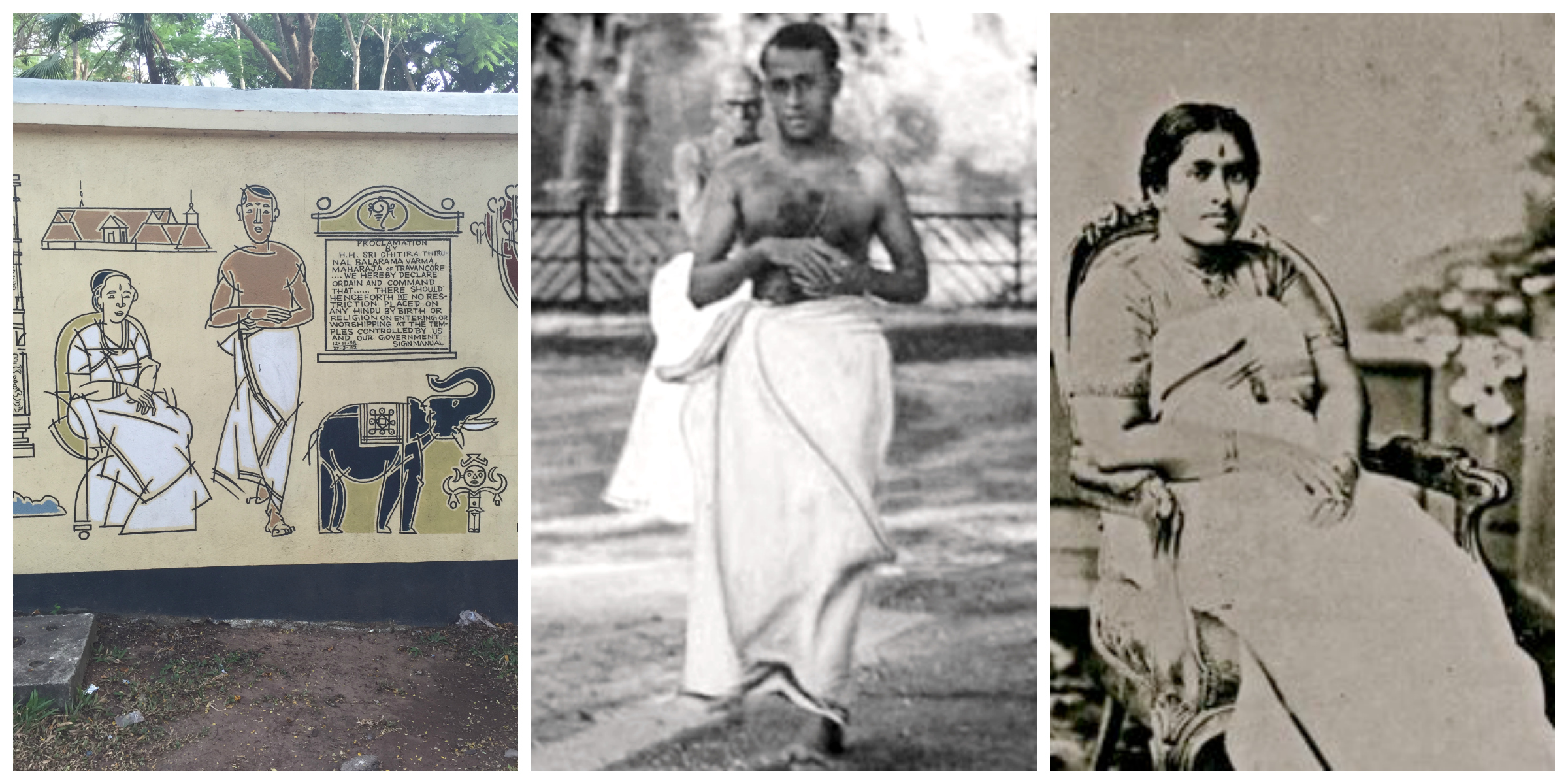

The mural series brings the disassociated history of Travancore into the daily life of the city dweller in a catchy neo-cubist style. These are quite "legible" for any viewer with a nominal understanding of Travancore's history. Murals, however, are almost facsimiles of popular historical photographs or contemporary painted narratives of Travancore rulers. In other words photographs, paintings, and painted murals that are widely circulated on the internet. See two such comparisons below.

Other mural panels are imaginative renderings of famous historical events such as the attack on Travancore by Tipu Sultan and (unrelated) suicide of Velu Thampi Dalawa.

All but one of these panels display the dates or any other factual details in text form associated with the historical events rendered. Indeed, the chronology of events have only been loosely followed. If you click through the first slideshow, you will notice that the most popular and powerful rulers are placed side by side to trace a genealogy that affords the first king Marthanda Varma and the last king Balarama Varma pride of place in the mural series.

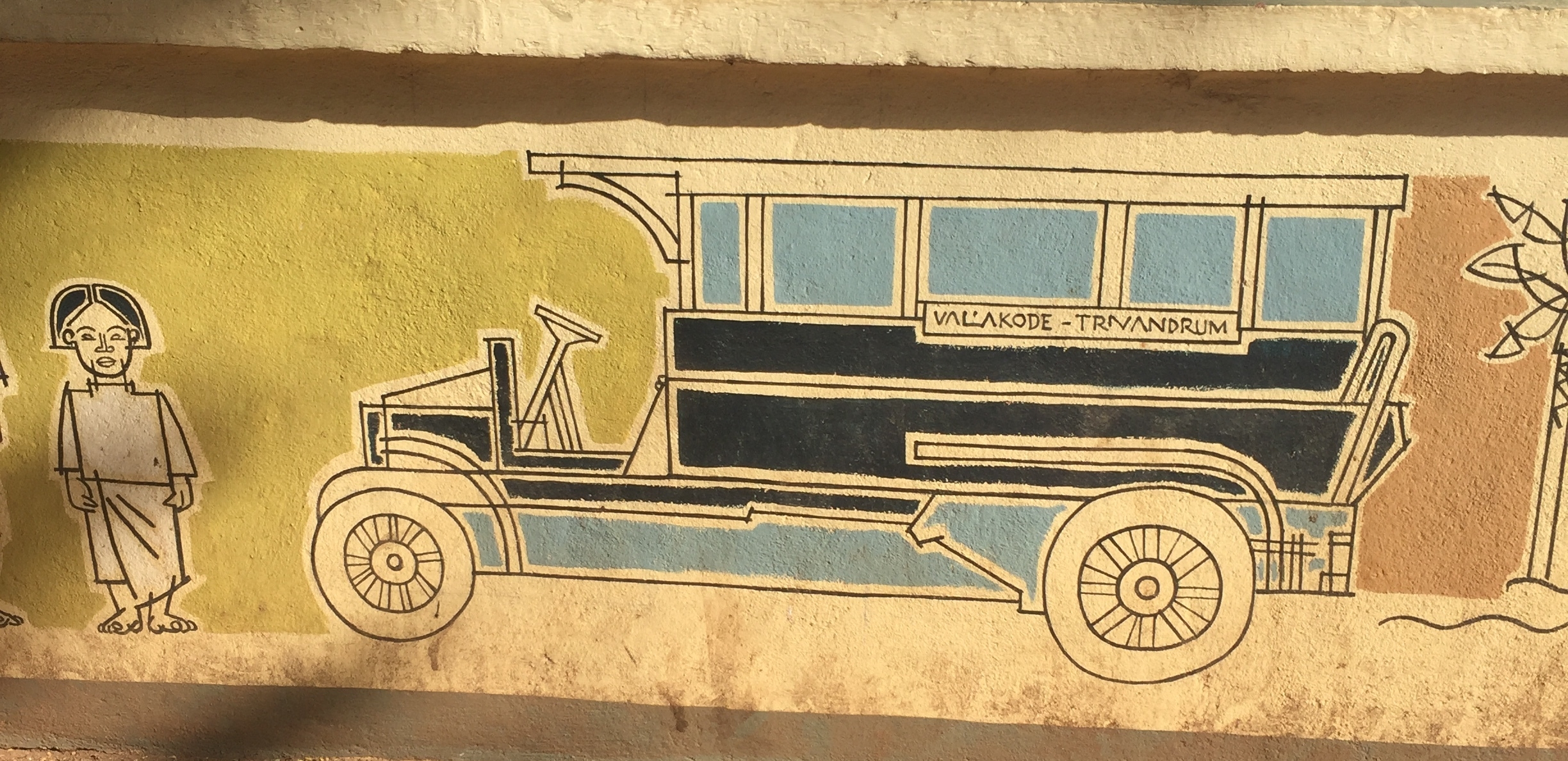

On the walls west of the main entrance to the palace grounds, historiography of Travancore kings gives way to political, cultural, and social accomplishments of colonial Travancore. These include images of architectural edifices, educational institutions, cultural symbols of royal power and more. (See some of them below.)

The western walls also show traditional colonial and early postcolonial lives of Keralan/Travancorean people. There is also one snapshot of Mahatma Gandhi and a handful of people in Nehru caps sitting beside a charka--a nod to the independence movement. But besides that vignette, it almost looks as if Kerala (or rather, Travancore) casually and easily slips from kingdom to postcolonial state under the effective guidance of the kings of Travancore. Indeed, no one else of any fame is portrayed in this series.

One could argue that the mural series having been painted outside Kanakakkunnu palace, one of the many palaces belonging to Travancore royal family in the early-twentieth century, mandates such a glorious and exclusive historiography. Yet, it is crucial to ask: What kind of history is the average Keralite in the capital city imbibing from these visual narratives? Why this narrative?

This reproduction of popular historiography--stories that are part of the popular culture of the state--is interesting since it appears to reiterate specific ideas of statehood and Keralan/Travancorean identity. The visuals here, filtered through an ethnic-nationalist lens, reifies the historic identity of the Travancore Malayali as one steeped in princely nostalgia, exhibiting pride over a distinctively Travancorean past.