Here's what happened on the map, in words (information below is paraphrased from India Office Records at the British Library - MSS Eur E313/7):

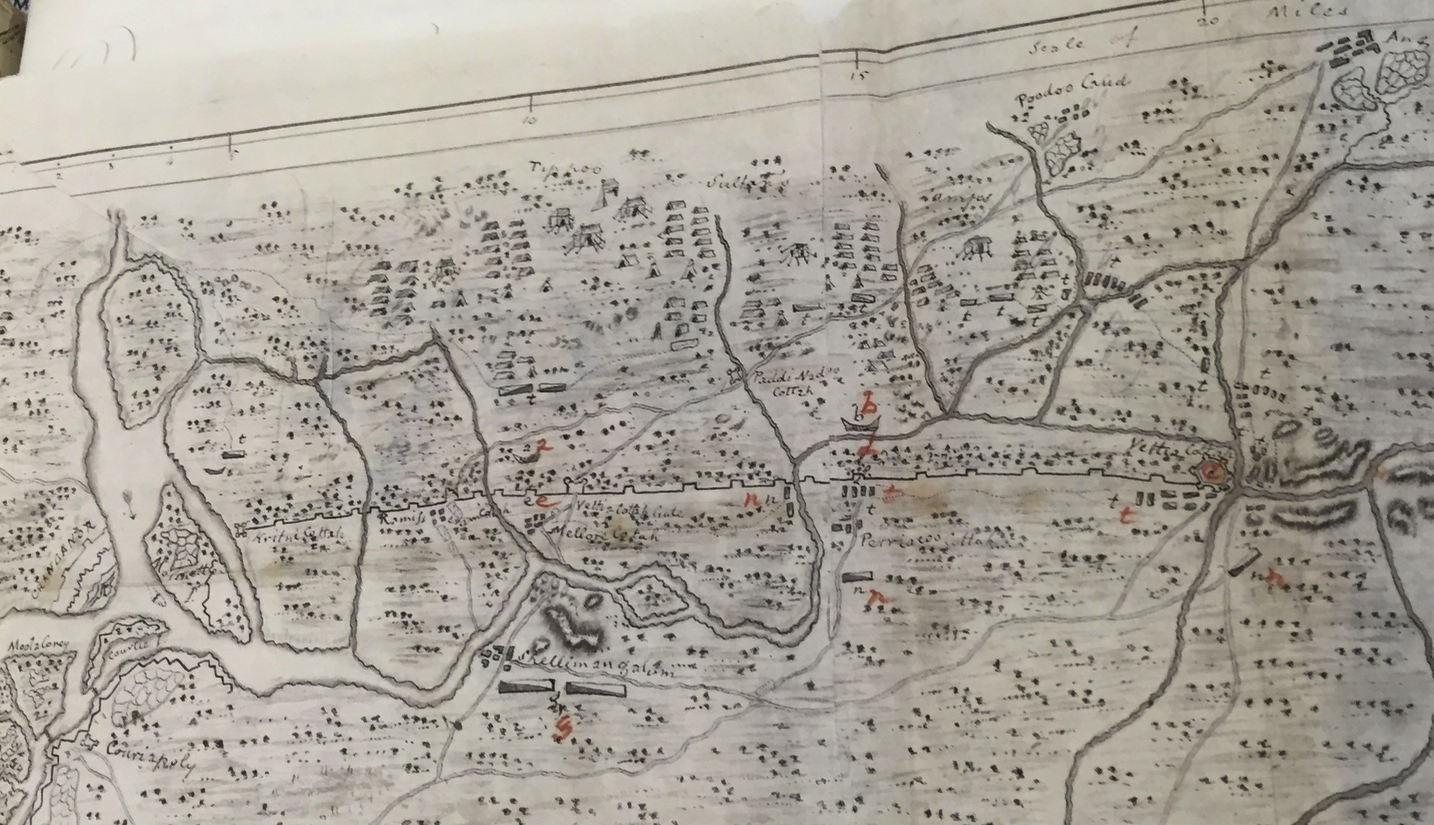

The attack on the Lines started on the 18th of December, with Mysorean horsemen approaching the Lines and hurling colorful abuses at soldiers stationed there to elicit from them a violent response. Having failed at that they erected batteries at a and b, and started bombarding the Lines, breaching them at d and e. By early afternoon breach d was practicable and they vigorously cut through the protective thorn bramble hedge, using bamboo laid with cotton to create a bridge over the trench so that the cavalry force could cross over. This mission, having taken a long time, made troops impatient. Seeing this, Tipu led the left flank to Vettia Cottah (the fort marked 'c'). He found a way around the hills nearby and through the bed of a stream, his infantry crossed over to the other side. But a cannon that he tried to take through the hills had to be sent back to breach d for its transport. The troops, however, came around the lines and walking back to breach d, helped their compatriots on the other side in building a path. With sufficient bamboo and cotton, an amicable path was now laid.

The Travancorean soldiers between points c and d, having been completely surprised by this line of attack, fled, but soon from the western end, groups of Nair soldiers and Conjecoots (archers) approached the invading army. Mysorean guns from the bastion was turned on the Travancoreans but, in only its second fire, one of the guns burst causing great loss of life and confusion amongst Mysoreans. Taking advantage of the mayhem, Travancorean soldiers approached with full zeal, charging them with bayonets. While the Mysorean troops took flight in apparent confusion, another group of Travancorean soldiers appeared at c. Mysorean soldiers now started gathering at the breach, many of them standing on the bamboos laid out on the ditch. But the gun burst had created a fire, which spread quickly towards the ditch laid with cotton, killing many of the soldiers crowded there. The author of this record dramatically discusses the "shouts of victory" from the Nairs who then proceeded, he says, to fling the enemy into the ditch as if into a furnace or killed them with bayonets and daggers.

Thousands of Tipu's troops died in the first attack on Travancore Lines. Tipu, himself, appears to have been seriously injured. The author of the record at the time thought Tipu was probably dead as he was said to have received a musket ball to his thigh and an arrow to his back. But Tipu obviously did not succumb to these injuries, as we well know. Mysorean soldiers captured during the siege, however, did confirm that the white horse found dead on the battle site was indeed Tipu's. Many of Tipu's personal objects were also gathered and taken to Travancore including: two strands of colours (state banners), one drum, and Tipu Sultan's silver mounted ivory palanquin. From in and around the palanquin, other objects were seized: a silver box holding 14-15 diamond and other valuable rings, turban plume made of jewels and ornamented with pearl pendants, a small French inkstand along with Tipu Sultan's Persian office seal that contained all his titles, his personal betel box, pistols with his name engraved on them as well as his sword. Considering the importance of the items recovered, it is evident that Tipu must have been in great danger and seriously wounded if these had been left behind.

On a related note, a lot has been said about Tipu Sultan's cruelty towards people inhabiting the regions he invaded, particularly tinged with a notion of a violent Islamism, both in the Company records as well as in some of the modern re-discovery of this colonial-era ruler. The link between religion and political violence in pre-modern India is a topic that is extremely complex and determined by local contexts as much as it is by transnational changes. Richard Davis (and others) have discussed the act of political violence in pre-modern India as processes of state action undertaken by all political actors regardless of region and religion. In this record that I have examined, we see such an an instance of violence against Mysore by Travancorean army. The record reports that not only were those stuck on the Travancorean side of the Lines captured in large numbers and mutilated or thrown into fires, but the Mysorean commanders killed in battle were brought back as trophies to Travancore. The report discusses how the son of Meer Sahib (Tipu's general) was found dead on site, and his head was decapitated by Nair soldiers to present to the Travancore king.

Following the failed first attempt on the Travancore Lines, Tipu Sultan came back with more artillery and infantry in March-April 1790. By April 15, Travancore Lines had capitulated to the Mysorean army without much resistance from Travancore-Cochin soldiers. It is said that his first ignominious defeat at the Lines had enraged Tipu so much that during the second attack, he instructed his army to pulverize the bulwark, which they did in parts for well over a month until May 1790. The way to Travancore was all but paved for Tipu when he had to rapidly withdraw from Malabar to return to his capital under the looming threat of a direct attack by the British. (This would be the third Anglo-Mysore War, 1790-2, that saw Mysore utterly defeated. Tipu entered into a treaty that not only saw him pledge two of his younger sons to the custody of Lord Cornwallis but also ceded half his newly-conquered territory to the Company.) Tipu Sultan never returned to south Malabar. Constant battles over territorial claims kept him well north of Nedumkotta.

As for the Lines, a large portion of it was razed by the British in 1809-1810 citing structural reasons. But as late as 1830s, British soldiers were posted on the Lines. Today, there is little left to see of this grand edifice. Mined for its bricks and land, Nedumkotta suffered the fate of many other historical structures in South Asia--near-total destruction and almost a complete erasure from public memory except in the stories and minds of those who continue to live around the remnants of the structure that stopped the Tiger of Mysore.