The Travancore Lines or Nedumkotta as it is called in Malayalam was a legendary bulwark built across Thrissur and Cochin districts of Kerala to stop attacks from north Malabar. Designed initially to restrict access of the Calicut Zamorin in the 1760s, it soon became an all-important barrier against the onslaught of Mysorean armies under Haidar Ali Khan and Tipu Sultan in the 1780s and 90s. Little remains of this edifice that once stretched from Pallippuram fort on the western seaboard near Kodungallur to Anamalai in the Western ghats, stretching across a distance of over 30 miles through Periyar and Chalakudy river plains. The destruction of this great embankment happened over time, but Nedumkotta's sorry fate was sealed in post-independent India, its remains destroyed for the construction of highways and railways, and mined for bricks and stones by locals and pulverized by companies for raw materials and real estate. The capitalist urges of the Indian state and benign neglect that led to the ultimate demise of Nedumkotta merits a critical examination but I will leave that topic for another blog.

Konor Gate

The spot breached by Tipu Sultan's army in 1789.

Instead, here I examine the first breach of Nedumkotta by Tipu Sultan's army in 1789. I came across details of the attack in the folds of a British Library record, replete with maps of the Lines and exact points of breach. I have since tried to trace the actual locations of the fortifications with limited success, but others have traced a skeletal schema of Nedumkotta--their journey can be found in this video. My visit to Konor gate, the spot that was breached by Mysorean army is forthcoming in South Asian Archaeology blog, found here.

But first, a little historical background on the Mysorean invasion:

The exceptional ambitions of Haidar Ali and Tipu placed them squarely against the other growing political force in the Indian subcontinent--the British East India Company. Following Haidar, Tipu was set upon a program of extensive military expansion with the intent of taking over not only the smaller kingdoms of South India but territories of the Marathas and the Nizam of Hyderabad. In the 1780s, Tipu's reign threatened all these powers simultaneously, resulting in the forging of a strange alliance headed by the British but in which all other South Indian powers participated. For Tipu, to whom the small kingdoms and chiefdoms of north Malabar and Kanara capitulated like dominoes in the early decades of his reign, these regions provided a crucial path into south Malabar and thereon to Cochin and Travancore. Travancore, a state of considerable wealth, was also a strategic region in Tipu's grand plan--the region's control would allow Tipu to launch attacks on the Carnatic, the English at Madras, and to areas controlled by Marathas and the Nizam with relative ease.

The fables surrounding the person of Tipu (largely concocted by the British and continued to be popular with some sections of Indian populace) as a religious zealot and despot begins in this time period. But these descriptions don't quite align with actuality (more about this will appear as a podcast soon!) What we do know from the hundreds of pages of communications surrounding Tipu in British records is that the British were extremely worried about Mysore's growing powers, and alarmed at the pace in which Tipu was extending his dominions.

In 1789, after capturing lands of Zamorin (Calicut and parts of Palakkad), and Thrissur from Cochin, Tipu marched with great confidence towards Travancore Lines, constructed by Travancore on land belonging to Cochin, to protect both kingdoms from northern incursions. It was a stunning edifice designed as a rampart by Travancore's Flemish general Eustachius de Lannoy to shelter soldiers and store artillery and gunpowder. It contained numerous wells for fresh drinking water, store houses, and underground caves. The north side of the Lines was lined with two protective layers--one, a thick hedge of thorny bramble, and the other, a trench of considerable depth and width.

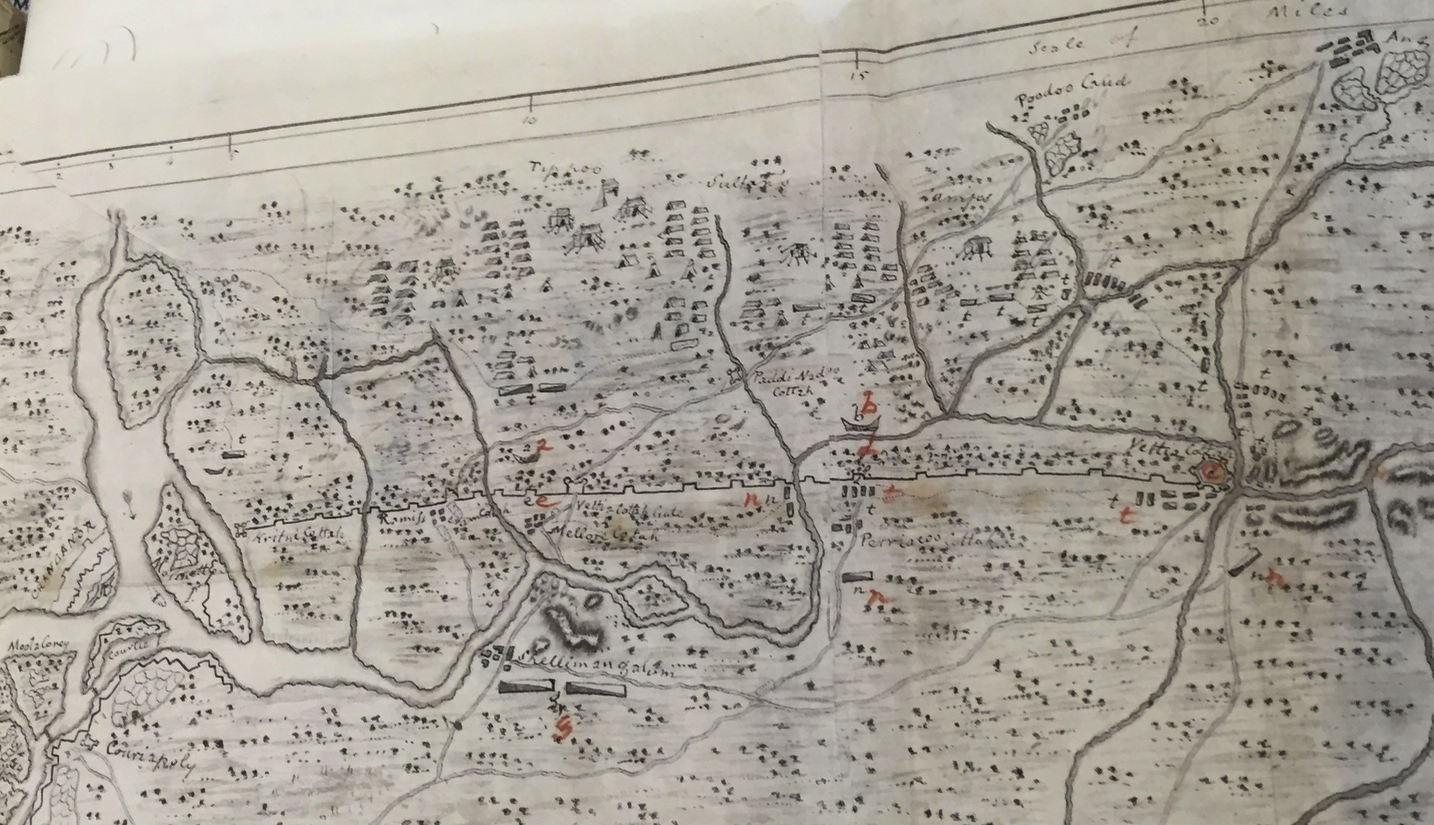

Tipu's first attempted breach of the Lines ended in a great loss for his army owing in some part to bad luck. Below is part of the map drawn by British Company officials of the Lines including points of breach, army camps, and other details. The middle upper portion of the map clearly shows Tipu's encampment that stretches over a significant portion of the land (I would venture to say that the army camp was spread over at least ten square miles). In the middle of the image, you see the length of Travancore Lines stretching from the fort of Kodungallur on the left, moving eastward towards the Ghats.

Map: The Attack on Travancore Lines by Mysorean Army in December 1789 (Image Courtesy: British Library, India Office Records, MSS Eur E313/7)

The important points in the map include:

'a': Tipu's battery 1

'b': Tipu's battery 2

'c': Vettah fort which was surprised by Mysorean attack

'd': the breach made from battery b

'e': another breach made from battery b but not practicable

'f': leading British officer Captain Knox's position before the attack

'g': Captain Knox's position after the attack

Half-shaded rectangles north of the Lines: Tipu's troops

Half-shaded rectangles south of the Lines: Travancore troops including Nairs & Conjecoots (archers)

Here's what happened on the map, in words (information below is paraphrased from India Office Records at the British Library - MSS Eur E313/7):

The attack on the Lines started on the 18th of December, with Mysorean horsemen approaching the Lines and hurling colorful abuses at soldiers stationed there to elicit from them a violent response. Having failed at that they erected batteries at a and b, and started bombarding the Lines, breaching them at d and e. By early afternoon breach d was practicable and they vigorously cut through the protective thorn bramble hedge, using bamboo laid with cotton to create a bridge over the trench so that the cavalry force could cross over. This mission, having taken a long time, made troops impatient. Seeing this, Tipu led the left flank to Vettia Cottah (the fort marked 'c'). He found a way around the hills nearby and through the bed of a stream, his infantry crossed over to the other side. But a cannon that he tried to take through the hills had to be sent back to breach d for its transport. The troops, however, came around the lines and walking back to breach d, helped their compatriots on the other side in building a path. With sufficient bamboo and cotton, an amicable path was now laid.

The Travancorean soldiers between points c and d, having been completely surprised by this line of attack, fled, but soon from the western end, groups of Nair soldiers and Conjecoots (archers) approached the invading army. Mysorean guns from the bastion was turned on the Travancoreans but, in only its second fire, one of the guns burst causing great loss of life and confusion amongst Mysoreans. Taking advantage of the mayhem, Travancorean soldiers approached with full zeal, charging them with bayonets. While the Mysorean troops took flight in apparent confusion, another group of Travancorean soldiers appeared at c. Mysorean soldiers now started gathering at the breach, many of them standing on the bamboos laid out on the ditch. But the gun burst had created a fire, which spread quickly towards the ditch laid with cotton, killing many of the soldiers crowded there. The author of this record dramatically discusses the "shouts of victory" from the Nairs who then proceeded, he says, to fling the enemy into the ditch as if into a furnace or killed them with bayonets and daggers.

Thousands of Tipu's troops died in the first attack on Travancore Lines. Tipu, himself, appears to have been seriously injured. The author of the record at the time thought Tipu was probably dead as he was said to have received a musket ball to his thigh and an arrow to his back. But Tipu obviously did not succumb to these injuries, as we well know. Mysorean soldiers captured during the siege, however, did confirm that the white horse found dead on the battle site was indeed Tipu's. Many of Tipu's personal objects were also gathered and taken to Travancore including: two strands of colours (state banners), one drum, and Tipu Sultan's silver mounted ivory palanquin. From in and around the palanquin, other objects were seized: a silver box holding 14-15 diamond and other valuable rings, turban plume made of jewels and ornamented with pearl pendants, a small French inkstand along with Tipu Sultan's Persian office seal that contained all his titles, his personal betel box, pistols with his name engraved on them as well as his sword. Considering the importance of the items recovered, it is evident that Tipu must have been in great danger and seriously wounded if these had been left behind.

On a related note, a lot has been said about Tipu Sultan's cruelty towards people inhabiting the regions he invaded, particularly tinged with a notion of a violent Islamism, both in the Company records as well as in some of the modern re-discovery of this colonial-era ruler. The link between religion and political violence in pre-modern India is a topic that is extremely complex and determined by local contexts as much as it is by transnational changes. Richard Davis (and others) have discussed the act of political violence in pre-modern India as processes of state action undertaken by all political actors regardless of region and religion. In this record that I have examined, we see such an an instance of violence against Mysore by Travancorean army. The record reports that not only were those stuck on the Travancorean side of the Lines captured in large numbers and mutilated or thrown into fires, but the Mysorean commanders killed in battle were brought back as trophies to Travancore. The report discusses how the son of Meer Sahib (Tipu's general) was found dead on site, and his head was decapitated by Nair soldiers to present to the Travancore king.

Following the failed first attempt on the Travancore Lines, Tipu Sultan came back with more artillery and infantry in March-April 1790. By April 15, Travancore Lines had capitulated to the Mysorean army without much resistance from Travancore-Cochin soldiers. It is said that his first ignominious defeat at the Lines had enraged Tipu so much that during the second attack, he instructed his army to pulverize the bulwark, which they did in parts for well over a month until May 1790. The way to Travancore was all but paved for Tipu when he had to rapidly withdraw from Malabar to return to his capital under the looming threat of a direct attack by the British. (This would be the third Anglo-Mysore War, 1790-2, that saw Mysore utterly defeated. Tipu entered into a treaty that not only saw him pledge two of his younger sons to the custody of Lord Cornwallis but also ceded half his newly-conquered territory to the Company.) Tipu Sultan never returned to south Malabar. Constant battles over territorial claims kept him well north of Nedumkotta.

As for the Lines, a large portion of it was razed by the British in 1809-1810 citing structural reasons. But as late as 1830s, British soldiers were posted on the Lines. Today, there is little left to see of this grand edifice. Mined for its bricks and land, Nedumkotta suffered the fate of many other historical structures in South Asia--near-total destruction and almost a complete erasure from public memory except in the stories and minds of those who continue to live around the remnants of the structure that stopped the Tiger of Mysore.